This post originally appeared on Women in Hollywood.

For five years I passed the signs on Venice at National; the only billboard sized image in Los Angeles with a woman behind a movie camera. Raised on a healthy dose of silent cinema, I could not believe that I had yet to see a Pickford film. I’d watched Charlie escape those Keystone Cops, seen Buster’s stunts while riding The General, even watched Douglas swashbuckle his way through the original Zorro. Why don’t I know more about Mary Pickford? I thought all those years, waiting for the light to turn green. Shaking myself from passive acceptance, I finally committed to learning Mary Pickford’s story.

|

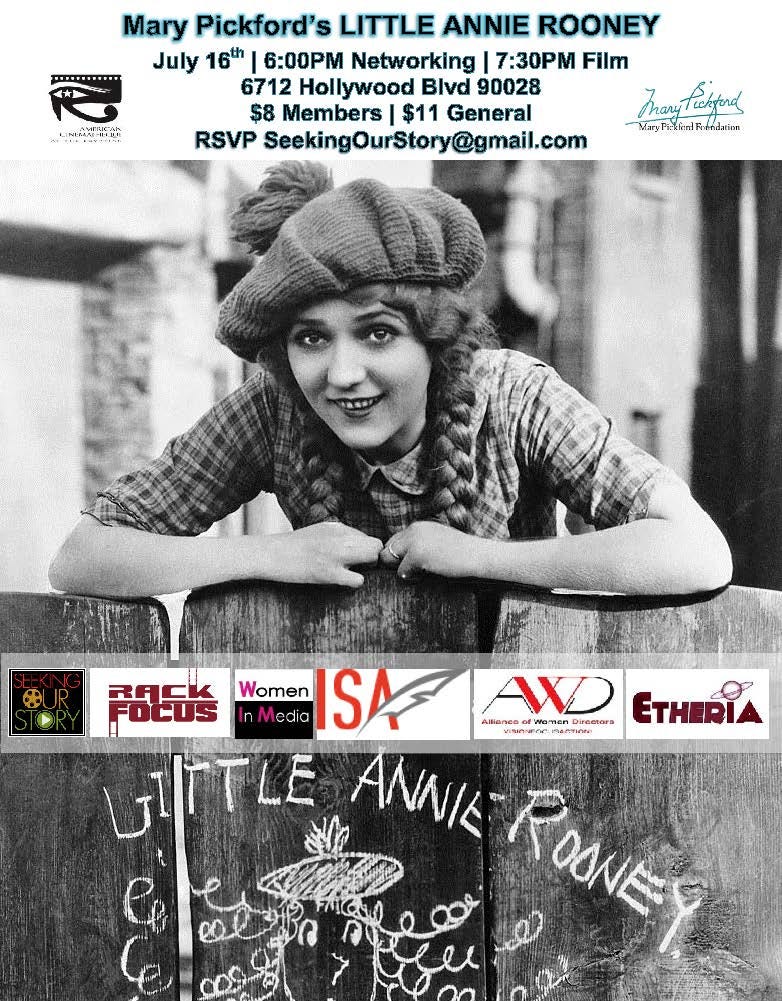

| Pickford on the set of Little Annie Rooney |

The first American movie star and second actress ever to take home an Oscar statuette, Mary Pickford appeared in over 250 film credits spanning from the inception of the art form through the introduction of talking pictures. Pickford controlled and shaped her own image by negotiating a producer’s contract in 1916 that gave her story and hiring rights over all of her pictures. She worked out of her co-owned Pickford-Fairbanks Studio, now known as The Lot in Hollywood, and employed a bevy of female support including the highest paid screenwriter of the time, Frances Marion.

Known for driving hard bargains that left studio chiefs near cardiac arrest, Pickford’s rising fortune grew from a need to financially support her mother and siblings. Born Gladys Louise Smith in 1892 in Toronto, she lost her father by age five, though he had abandoned his children years before. Her mother, Charlotte Hennessey, struggled to keep the family afloat and young Gladys started performing in Toronto repertory theater along with her younger sister, Lottie and brother, Jack. The family moved to New York for Gladys, now Mary, to debut on Broadway. Through producer David Belasco, she was reborn on the American stage as Mary Pickford. Though well received on Broadway, the Pickford’s needed income outside of the regular season, and Mary began appearing in the still gestating pictures business. She became a contract actress for the Biograph Company in 1909 and acted in numerous silent short films before moving her talents to Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players in 1913.

When renegotiating her contract just three short years later, Pickford set a record salary of $10,000 a week with project approval and hiring control to boot. In an industry that offered half, she demanded double and in doing so earned the respect and loyalty of the men she worked for. Moreover Pickford gained direct access to her fans, or “friends” as she called them in her public interviews. She understood her audience and learned quickly that her success depended on their love and approval. Pickford traveled around the country in person, selling war bonds and even acting as honorary colonel of the 143rd Field Artillery during World War I.

Little Annie Rooney (1925) fit the mold to perfectly please Pickford’s legion of fans. Appearing in her prototypical role as a child, Pickford’s “Annie” is a tenement tomboy in multi-ethnic New York, recreated entirely on the back lot at Pickfair. The film showcases her comedic chops and unique ability to play endearing, heartfelt characters of a younger age. As quoted in the May 1926 issue of Everybody’s Magazine, “I was forced to live far beyond my years when just a child, now I have reversed the order and I intend to remain young indefinitely.” She produced, starred in and even wrote (under pen name Catherine Hennessey) this comedy adaptation of the Annie Rooney cartoons, ensuring that the picture followed the formula she employed to dominate the box-office and earn the title of “America’s Sweetheart.”

|

| Tess of the Storm Country (1922) - Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences |

Pickford welded her immense power responsibility, always mindful of her fans as well as her fellow filmmakers. She told Photoplay Magazine in 1924, “I am no longer in pictures for money. I am in them because I love them. I am not in vain. I do not care about giving a smashing personal performance. My one ambition is to create fine entertainment.” As one of four founders of United Artists Corporation in 1919, Pickford controlled the distribution and marketing for The Mary Pickford Company films as well as pipelined sales that created direct proceeds for other creatives. In 1921 she created the Motion Picture Relief Fund, a pre-union support program for industry members in need that lead to the construction of the Motion Picture House and Hospital in 1942. A founding member of the Academy of Motion Pictures, Pickford was the only woman representative included in the 36 original board invitees of 1927. She won an Oscar for her role in Coquette, a 1929 sound picture, and also received an honorary Oscar for her contributions to the art of motion pictures in 1976. Pickford’s legacy lives on through the Mary Pickford Foundation, formed in 1971 with the mission to further Mary’s “commitment to her craft, her community and her philanthropy while inspiring future generations of women and filmmakers.”

After finally seeing Pickford on screen at The American Cinematheque’s screening of Sparrows (1926) I am convinced that Pickford is not only one of the most gifted dramatic talents of the silent era, but also a brilliant comedienne. Truly a star of the public, her playful style assures us that there will be a happy ending. Perhaps the non-threatening air displayed in her work also helped her succeed in winning the hearts, and pocket books, of studio executives and industry leaders. Mary’s story, and the stories of many women in early cinema, helps to guide my path as a filmmaker. We must commit to seeking their stories, to claiming our inheritance as a woman making movies today.

Saturday, July 16, Seeking Our Story screens Mary Pickford’s Little Annie Rooney, a co-presentation with The Mary Pickford Foundation and the American Cinematheque’s Rack Focus Initiative. Networking starts at 6:00PM presented by Women In Media, Alliance of Women Directors, The International Screenwriter’s Association, and Etheria Film Night in conjunction with a display of Mary Pickford Belongings and Memorabilia from the Tinsel And Stars Collection. At 7:30PM, the Pickford Foundation hosts a panel with commissioned composer Andy Gladbach followed by the feature presentation. More information and tickets here.

Samantha Shada is a Los Angeles-based director. She programs Seeking Our Story screening influential films directed by women.