Syndromes and a Century and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives are a beautifully complementary pair. One takes place predominantly in daylight, the other is shrouded in darkness. One is set in modern hospitals, the other a rural home. Both examine history through personal, national, and spiritual lenses, while forcing the viewer to consider the most minute tangible details of the present. Neither title is particularly descriptive of what the films are about. The first-time viewer could hardly be blamed for lack of better ways to summarize them, though. The filmmaker behind both, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, is not unconcerned with story, but his command over the sensual experience of the movies so pleasingly lulls one into a sense of contentment that the threads may soon evade our grasp. They are essential theatrical experiences, commanding our attention and assuring us a couple hours free from other distractions.

Both films are less plot-driven than place-driven. Weerasethakul has said Syndromes is about his parents, or at least was intended to be. The first half of the film, which takes place some forty years before the second, was to be the main setting for the entire film. But as Weerasethakul cast the film and found its shooting locations, the concept evolved, with a stark country hospital/city hospital divide to further separate the spaces. It still follows first a female doctor, then a male (his parents were both physicians), with little direct connective tissue between the times and places. More so than characters, conversations recur. Doctors are interviewed in the same format. In the first half, a character’s past life is discussed; in the second, a future life. The forward-looking teen says that he has his entire life planned, but it will take one year more than he has to live. He’ll have to count on his next life.

Despite its title, reincarnation remains on the periphery of Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Weerasethakul has few laugh-out-loud moments in his films, but he has a wicked, sometimes perverse, sense of humor (he’s not “above” an erection joke). The title, as direct and explanatory as Snakes on a Plane, proves remarkably unhelpful here. At no point is it said or suggested that Uncle Boonmee (Thanapat Saisaymar) can remember anything before this life. This life has proven difficult enough. Suffering from kidney disease and recognizing his days are numbered, Boonmee gathers his remaining family - sister-in-law Jen (Jenjira Pongpas) and nephew Thong (Sakda Kaewbuadee) - to help him approach death. Their reunion conjures the spirits of Boonmee’s late wife and son.

Uncle Boonmee won the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, surprising many who still struggle to pronounce its director’s name and didn’t know what to make of this film with red-eyed ghost monkeys and lascivious catfish. These elements earned the film its share of traction amongst genre-heads and meme generators, but Weerasethakul meets this strangeness with acceptance. His characters don’t think these creatures unusual. When Boonsong, Boonmee’s dead son, joins a family dinner in the form of a monkey, his aunt’s only question is, “why did you grow your hair so long?” The soundtrack, packed with crickets and frogs and other creatures of the night, suggests we can never know what all lives in the darkness, while guiding us into a sense of complacency and peace. It’s the feeling of being a child at night, uncertain of what’s under the bed, for once feeling protected by it.

Like Syndromes, Uncle Boonmee transformed from its initial conception, which was to be a straight adaptation of the 1983 nonfiction book A Man Who Can Recall His Past Lives. Weerasethakul instead used some of its structure, filling the details with his own imagination. The Boonmee of the film may not remember his past life, but he remembers the life he has lead, chiefly his regrets from killing communists while in the military. Both Uncle Boonmee and Syndromes use photographs to fill in what cannot be filmed, but once again the past/future divide comes into play. In Uncle Boonmee, the photos are meant to illustrate his time in the army (they’re actually production stills from a Weerasethakul short); in Syndromes, the photos are of a hospital in the midst of construction to which the doctors are considering relocating. The original Thai title of Syndromes and a Century translates literally to "Light of the Century," but which century? Is it indebted to the 20th, where half the film is set, or to the the 21st, where the other half lives and of which its characters dream?

Syndromes and a Century grows (even) more abstract by the end, abandoning dialogue to situate its characters in spaces we’ve seen previously while the camera roams freely through them. In its most mesmerizing portion, the camera considers an air vent that winds through the room like a hose. It’s a strange object that grows stranger as the camera rotates around it, the ominous, humming music growing more intense. What seems to be a maintenance room turns into something out of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Such are even ordinary spaces in Weerasethakul films; to communicate the beauty and wonder he conjures in a cavernous journey late into Uncle Boonmee would be in vain. The interior constellation must be seen to be believed.

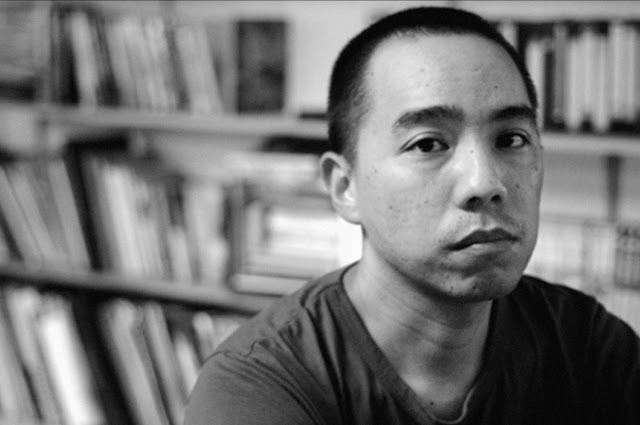

Both films screen Thursday, October 20th at the the Aero Theatre as part of a citywide celebration of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s work. A discussion with the director follows.

Scott Nye is the editor-at-large at Battleship Pretension and co-host of the CriterionCast podcast. He can regularly be found at Los Angeles's many repertory theaters, or on Twitter @railoftomorrow.